Word embeddings vs./& WordNet

Preview

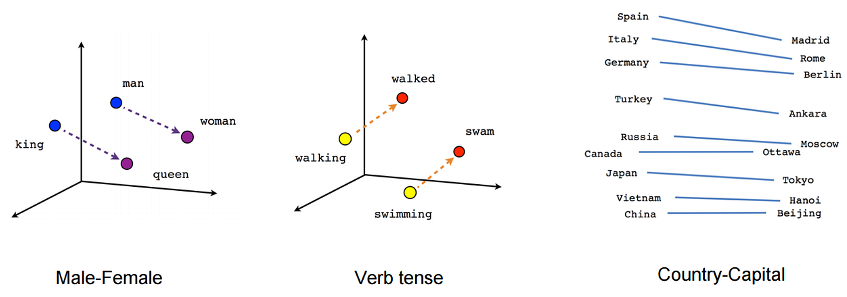

Word embeddings, is a way to represent words as multi-dimensional vectors that capture various semantic information. Words that are semantically close to one another would be close to each other in word vector space. Many common relationships such as gender, tense correspond to arithmetical operations one can perform on word embeddings.

Figure 1: Word embeddings

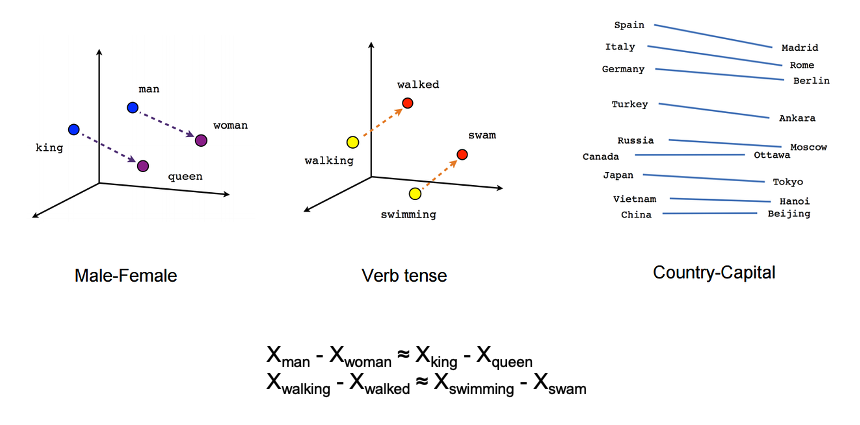

Wordnet, as its name suggests, is a huge network of words connected by sense relations, and its highlight is the synsets and rich sense relations and that are manually labelled.

Today we will cover the rationale of these 2 methods, and their applications in detecting semantic shift.

Figure 2: WordNet

Word embeddings

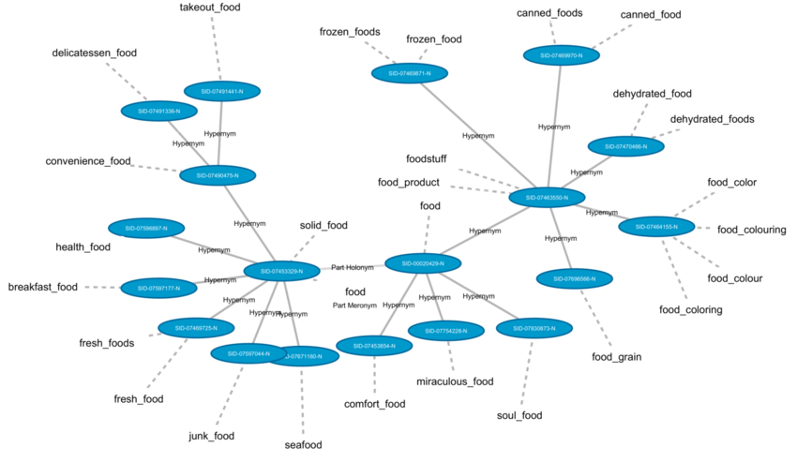

Let’s start from word embeddings. Representing words with vectors has been developed for some time, so it contains a variety of word embedding methods.

Static Word embeddings are commonly categorized into two types, depending on the strategies used to induce them. Count-based methods generally use corpus-wide statistics such as word-context co-occurrence counts and frequencies.

Then with the availability of large corpora and the development of computational linguistics, prediction-based methods emerged. In 2013, Mikolov from Google proposed the word2vec model to obtain dense distributed word vetors containing syntactic and semantic information.

The recent trend in word embedding is to learn the contextualized word embeddings. In these methods, each word is assigned by a representation that is a function of the entire input sentence, which make embeddings different in different linguistic contexts for 1 word. Among those, BERT models are the most frequently used monolingual model, and XLM-R models are the most preferred multilingual models.

Due to time constraints, today I’ll focus on two mainstream methods Word2vec and BERT. And their application in detecting semantic shift.

1. Word2Vec

We all know that embeddings are some magical vectors that are able to represent semantics using numbers. But how does this happen?

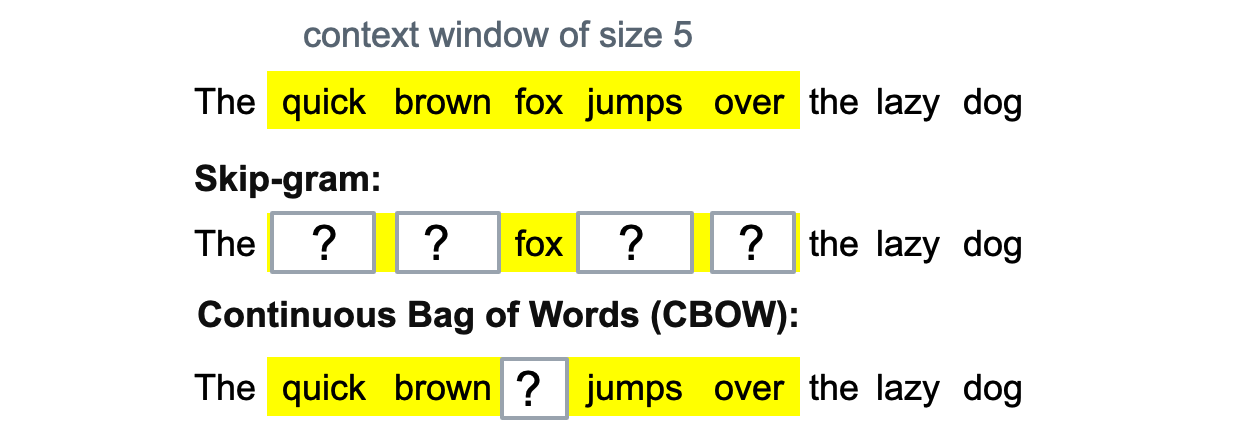

Here’s a brief explanation of how we get word embeddings using word2vec. Word2Vec offers two model architectures: Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) and Skip-Gram. Both are shallow neural networks, meaning they consist of the input layer, only one hidden layer, and the output layer.

1.1 Skip-gram vs CBOW

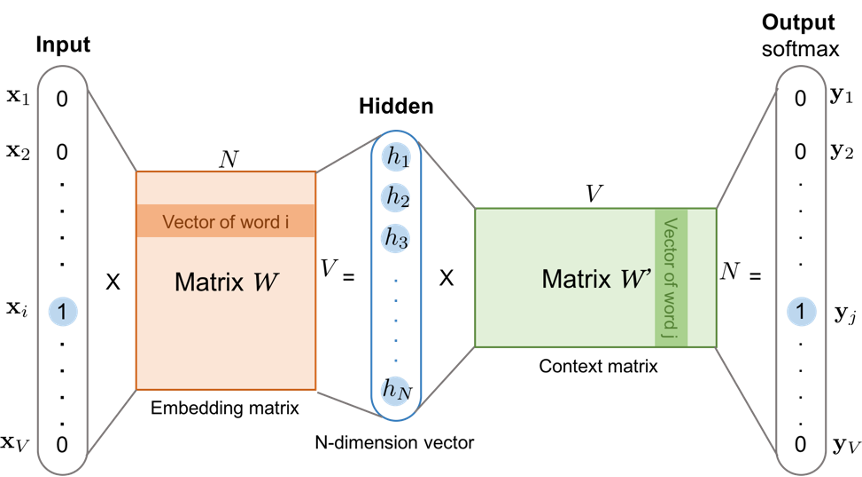

Figure 3: The skip-gram model based on narrow neural network. Both the input vector 𝑥 and the output 𝑦 are one-hot encoded word representations. The first weight matrix is preserved as trained word embedding.

Let’s look at Skip-gram first. The input layer receives a one-hot vector of one target word. Then it is multiplied by a weight matrix known as embedding matrix to transform to hidden layer. And then multiply another weight matrix and use softmax function to get a probability distribution of the Vocabulary in the output layer.

Figure 4: Word2Vec: Skip-gram vs. CBOW

For Skip-gram model, the task is to predict the context words given the target word, so The model is trained to minimize the prediction error of the context words. after training we preserve the first weight matrix between input and hidden layer as Embedding matrix.

Situation is similar for CBOW model, the only difference is that its task is to predict the target word based on its context.

1.2 Word2Vec in Semantic shift detection

Let’s take a look at the application of word2vec in semantic shift studies.

After Mikolov proposed Word2vec in 2013, in 2014 Kim and his colleagues employed prediction-based word embedding models to trace diachronic semantic shifts as the first.

Model: They pretrained the skip-gram model, with a window size of 4 and dimensionality of 200 for the word vectors.

Data: And the data include 10 million 5-grams sampling from the English fiction corpus of Google Books Ngram for every year from 1850–2009. But to mention, For the analysis, they treat years before 1900 as an initialization period and begin their study from 1900 on yearly basis.

Measure: They used Cosine distance as a measure of similarity between word embeddings.

Tasks: The author focus on 2 tasks of semantic shift detection:

-

identify words with meaning change

-

identify period of change

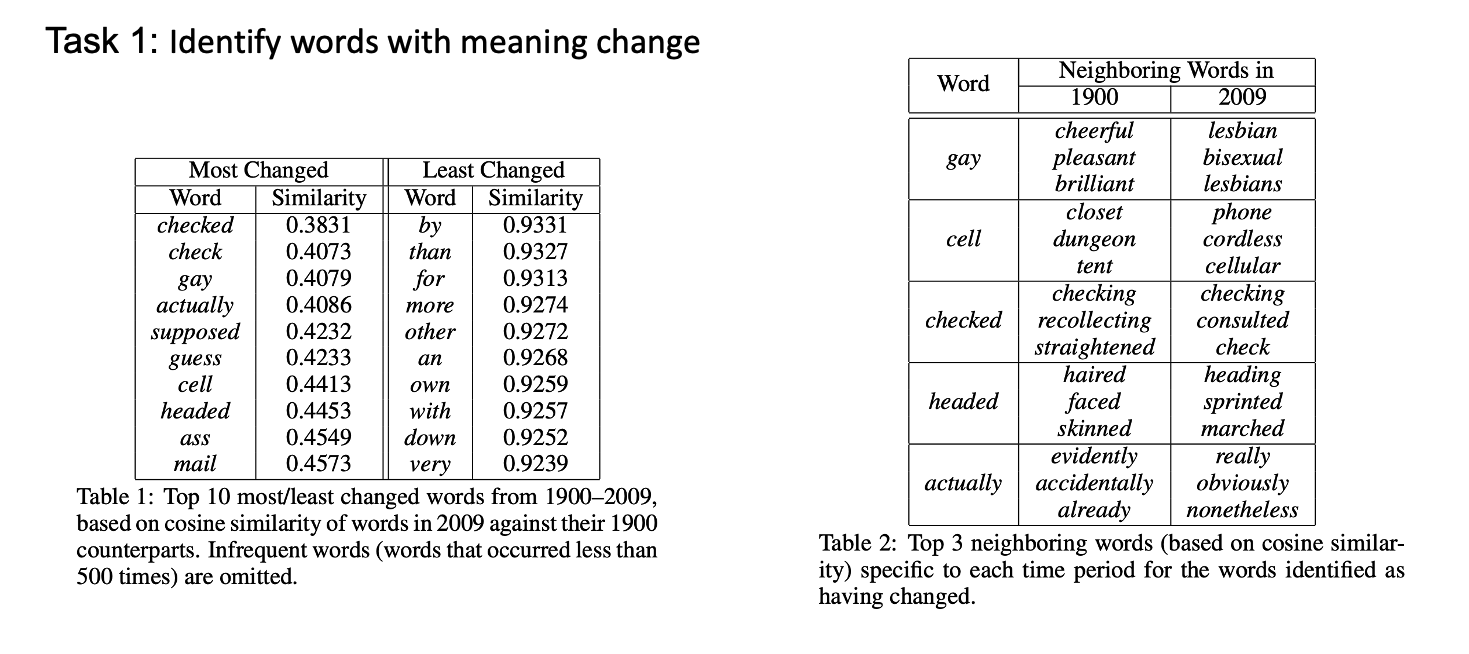

Figure 5-1: Word2Vec in DSS

For the first task, they compared the cosine similarity between same words across different time periods, and based on the cosine similarity of words in 2009 against their 1900 counterparts, they have this ranking of the most changed word and the least changed word. It agrees with intuition that almost all of the least changed words are function words. And for the most changed words, they find the top 3 neighboring words for 1900 and 2009, and manually analyze the semantic change based on some example sentences from certain time period.

Figure 5-2: Word2Vec in DSS

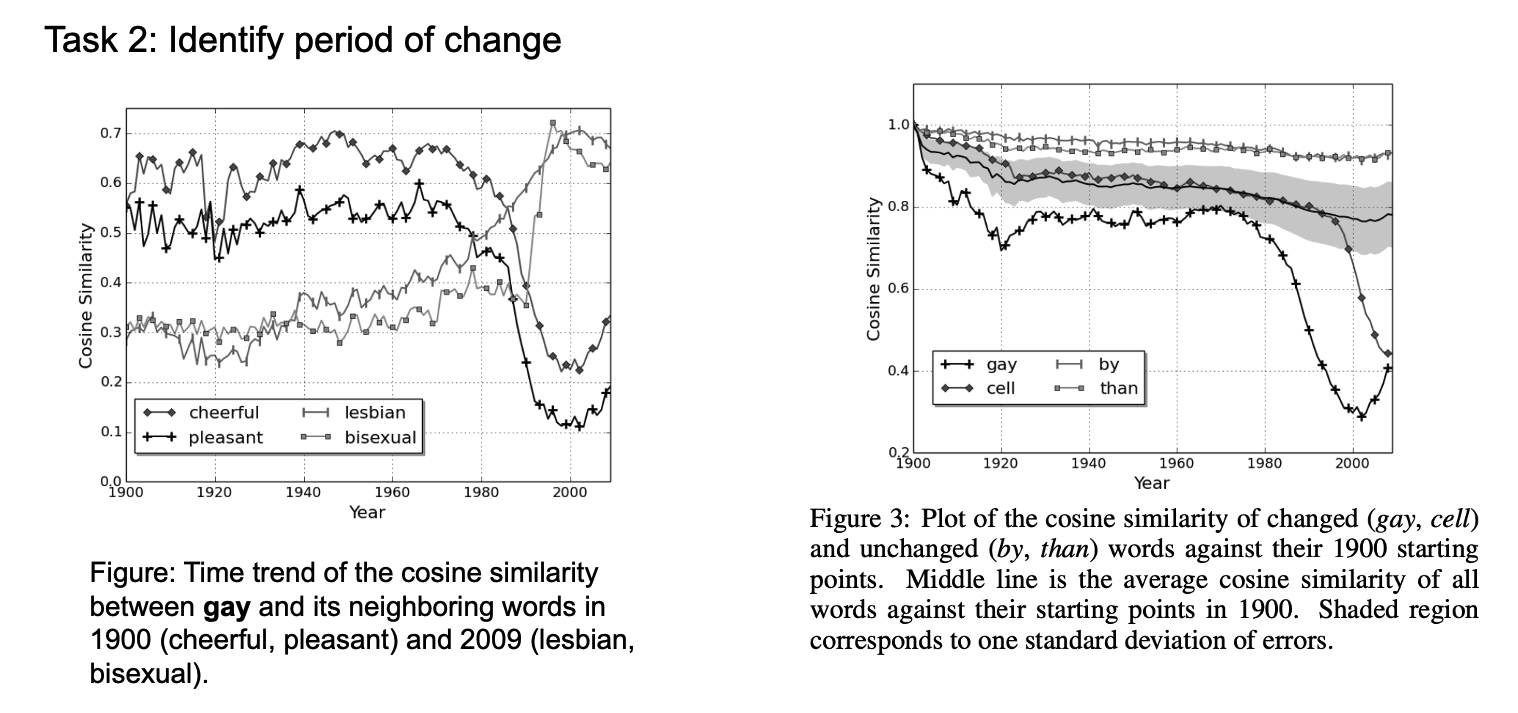

For task 2, they compared the cosine similarity between a word and its neighbor words from different period, thus can identify when a word changed; Here the meaning change begins in around 1970 or so.

Besides, they also analyzed the cosine similarity of a word against itself from a reference year, here the initial year of 1900. Here we can see the word gay and cell changed dramatically at the end of 20 century, while by and then remains stable.

2. BERT

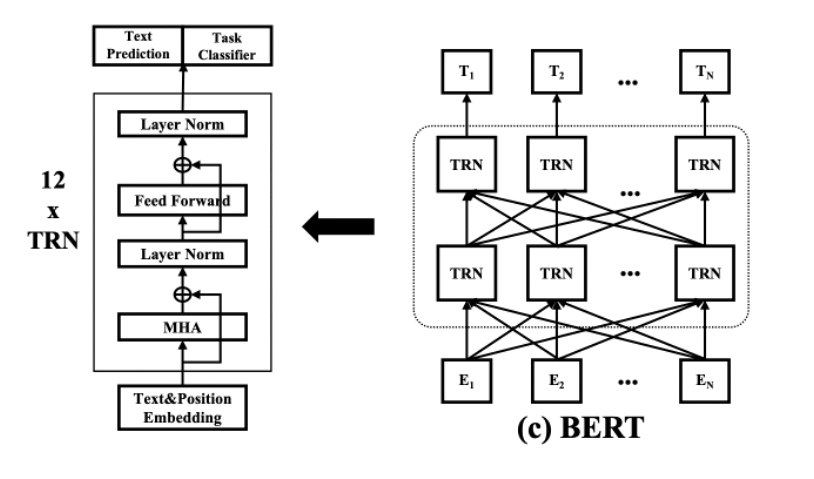

BERT is much more complicated, so we will not get deep into the fine structure of BERT model. Here We can just consider it as a deep neural network with 12 transformer-based hidden layers.

Figure 6: BERT

Compared to word2vec, BERT is pre-trained on a large corpus using two more complex tasks: masked language modeling (MLM) and next sentence prediction (NSP), so that it learns rich contextual representations for words.

Here’s a very brief explanation of How we get the contextualized word embeddings from BERT: The input representation of a token is passed through multiple layers of the Transformer architecture.

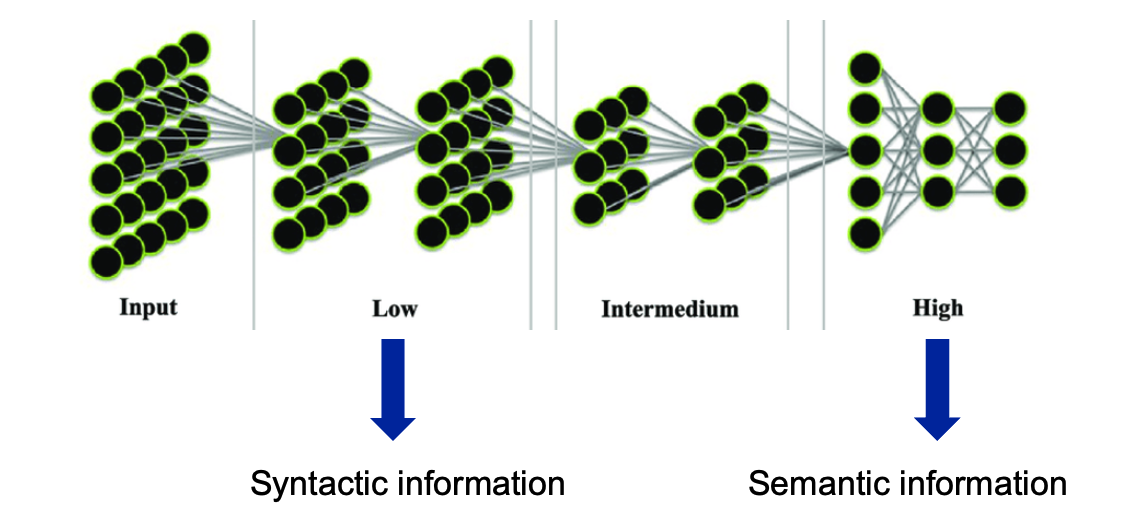

Figure 7: Layers selection in BERT

As BERT processes input tokens through its multiple layers, each layer outputs its own version of embeddings for the token. These embeddings can be accessed individually depending on what kind of information you need:

- Lower layers tend to capture more syntactic information, such as part-of-speech tags.

- Higher layers tend to capture more semantic information, relevant to specific tasks like sentiment analysis.

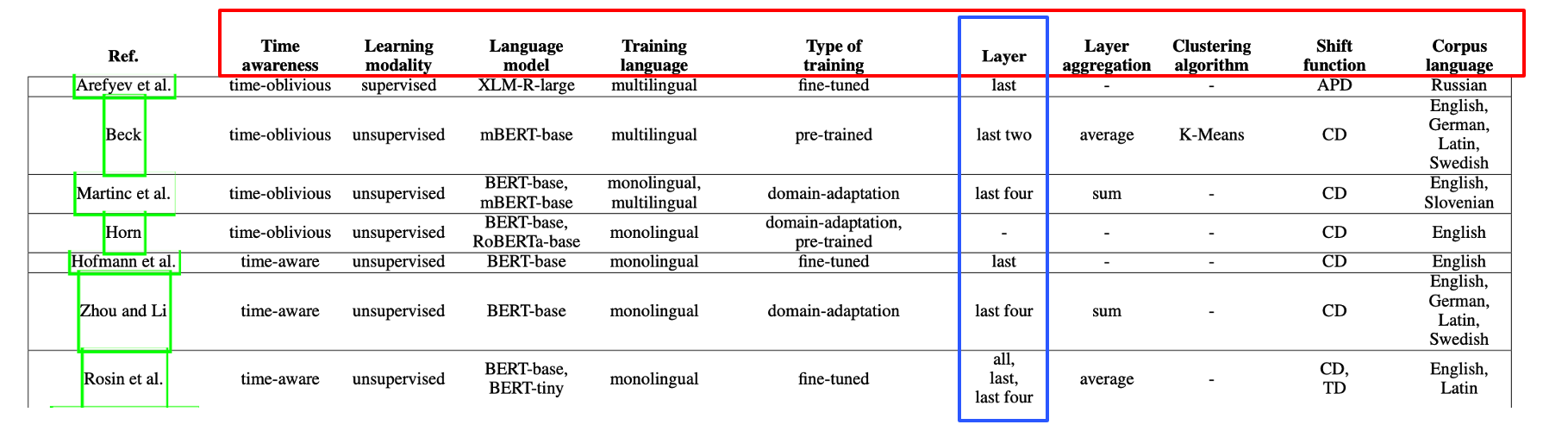

2.1 BERT - Configuration

And The emergence of Contextualized word embeddings has enriched the research methodology a lot, because there are so many aspects we can configure.

Figure 8: Summary view of some form-based and sense-based approaches

For example, we can choose different large language models and training methods, we can extract word vectors from different layers (for semantic shift usually we choose the higher layers(the last layers) because they contain more semantic information), each configuration has its own advantages and serves different task purposes.

In a word, the contextualized embeddings offer a significant advantage over static embeddings because embeddings are dynamic for each sentence, this can address the issue of polysemy. And through complex training task, the embeddings are able to capture more deep information and thus can detect more subtle change than static embeddings.

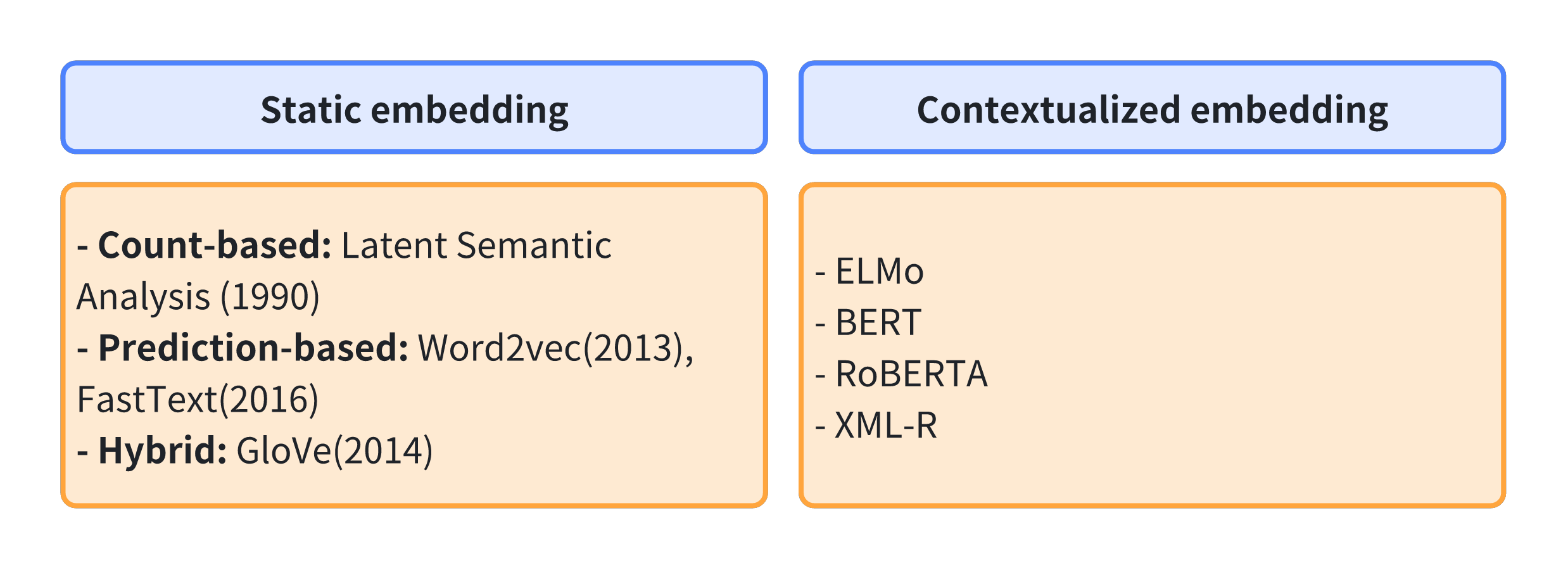

Wordnet

Now let’s move on to wordnet. As for wordnet, I’ll first cover basics of its structure, and then show an example of what it looks like to browse WordNet online.

WordNet is a large lexical database of English. It contains information of 4 type of words: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. For each word, Wordnet provides its Part of Speech tag, definitions in points, synonyms, and example sentences. So, to some extent we can use it as a dictionary.

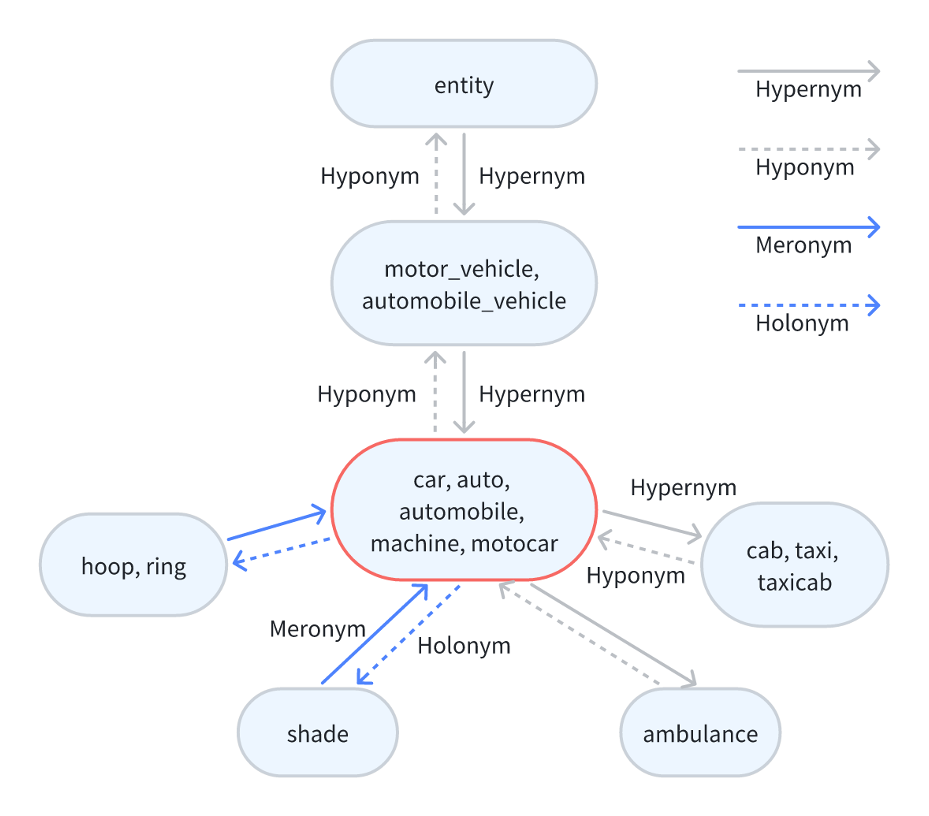

But the crucial difference between wordnet and dictionary is that, words in wordnet are grouped into sets of cognitive synonyms (what we call synsets), and those Synsets are interlinked by various conceptual-semantic and lexical relations.

Here I take these nouns as an example to explain the hierarchical structure of wordnet and relations among synsets. The main relation among words is synonymy, as between the words car and automobile here, and with other synonyms they consist of a synset, every node here reprensents a synset.

Figure 9: An example of wordnet synset

Other frequently encoded relations include super-subordinate relation(hypernym – hyponym) and part-whole relation(meronym – homonym). For example, taxi is hyponym to car, while car is hypernym to taxi and ambulance. And ring and shade are meronyms to car, because they are components of a car, while car is holonym to ring and shade. And other types of sense relations, like antonymy between “increase” and “decrease”, and derivation between “destroy” and “destruction”, which is also a cross-POS relation.

1. Wordnet online

WordNet is publicly available online, so you can browse through it yourself, and I’ll quickly show what that looks like here.

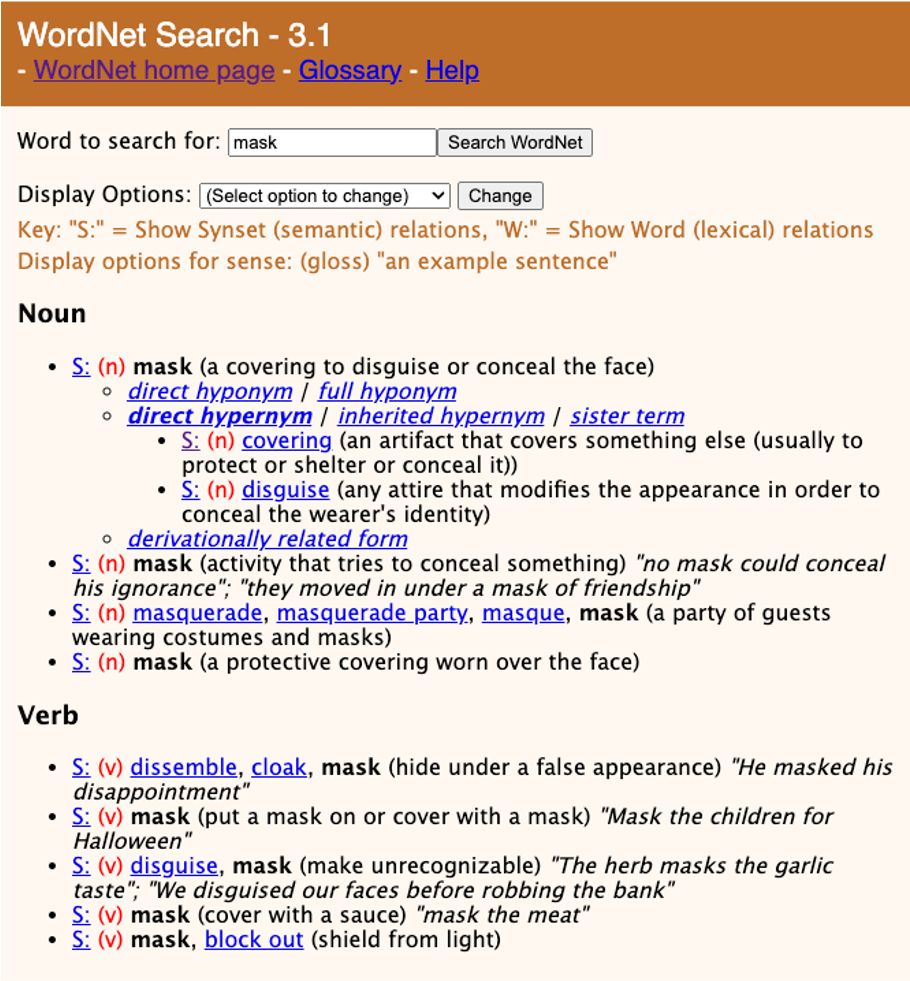

Figure 10: Online WordNet

Each unique word in WordNet has its own entry, and that entry may contain one or more senses or different meanings. For example, as shown in the entry here, the word “mask” can be used as a noun or a verb, and in multiple different ways.

Each sense’s listing in WordNet has:

- a gloss;

- a list of synonyms if any are available, usually referred to as synsets. Here “masquerade”, “masquerade party”, and “maskque”, all being used to refer to the concept of a party of guests wearing costumes and masks and they form a synset;

- sometimes examples of how the sense would be used in a sentence. For example, for the first verb sense we have “He masked his disappointment”;

- and sense relations folded under the Key “S”.

2. Wordnet embeddings “Wne2vec”

2.1 Measure semantic similarity

Semantic similarities and relatedness between words can be determined by calculating the path distance or gloss overlap between associated synsets.

Apart from the calculation method, I want to introduce you this interesting method that transform the graphical Wordnet to word vectors. It’s called Wnet2vec, proposed by Saedi in 2018. It uses the path distance, the distance between 2 nodes to evaluate the strength of semantic affinity of two words, which is quite consistent with our intuition.

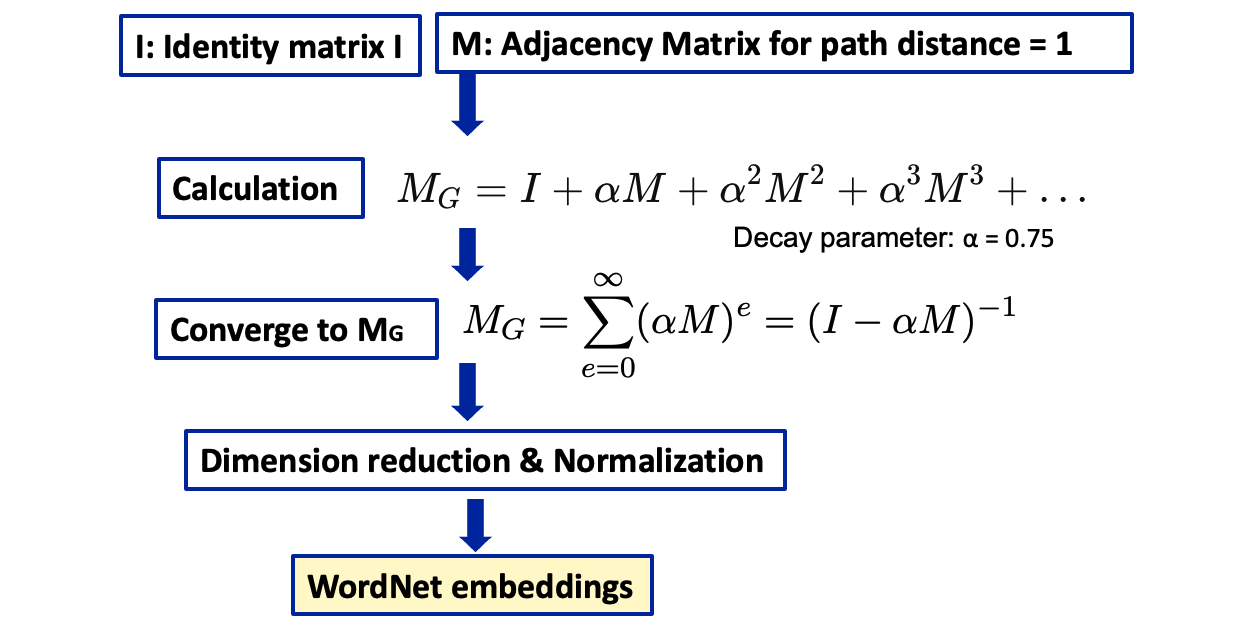

Here is the key procedures of how we get wordnet embeddings. Imagine a huge grid (matrix) where every word in WordNet corresponds to a row and a column. We first add an identity matrix I with 1 at diagonal, to ensure that the transformation considers each node’s relation with itself. Then we create an Adjacency Matrix for path distance = 1, based on the relation two words are directly connected in WordNet. Then we do the calculations until it converges into matrix MG, which can be obtained using this equation. Finally after dimension reduction and normalization we get the Wordnet embeddings.

Figure 9: Wnet2Vec. Here we use the setting that achieved the best result from this paper: α = 0.75; And we assigned different weights to different relations, hypernymy, hyponymy, antonymy and synonymy got 1, meronymy and holonymy 0.8 and other relations 0.5.

2.2 Evaluation

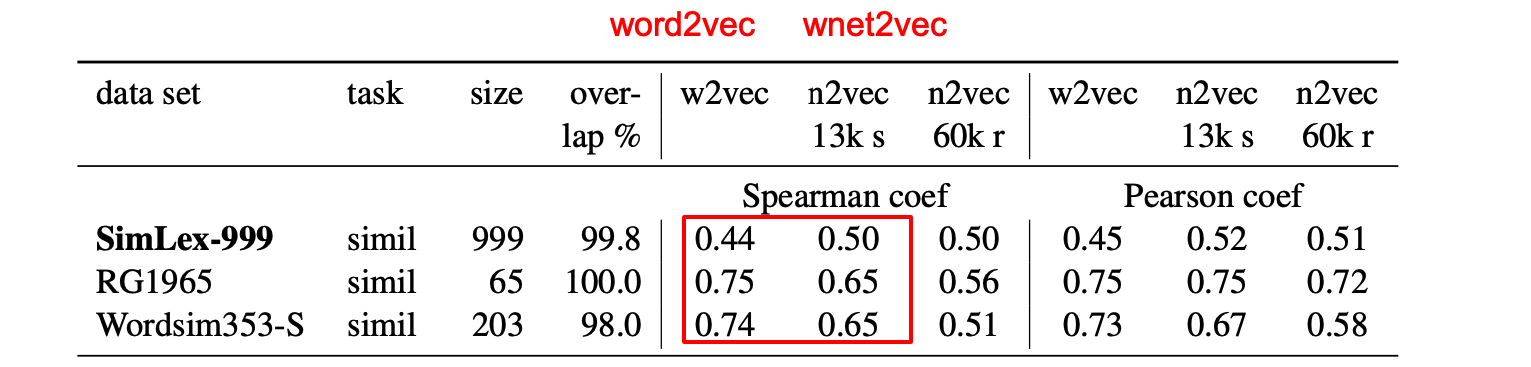

Now we got the word embeddings from wordnet, we need to assess its quality. To do so, the researcher use a large test data set SimLex-999, containing a list of pairs of words, with similarity score range from 0-1, and 2 smaller dataset.

Guess: What do you think the Wordnet embeddings perform in the task of determining semantic similarity between words? Compared to Word2vec, the static word embedding? (The outcome is compared to the gold standard scores in test datasets using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. )

Figure 10: Evaluation comparison between word2vec and wnet2vec

As we can see, for the largest and formalist test dataset the performance of wnet2vec was around 15% superior to the performance of word2vec. Even with those much more smaller test set built under less standard procedure, the wnet2vec still showed competitive performance even though their score were not superior to word2vec.

This indicates that wnet2vec can capture semantic information effectively and are competitive when compared to text based embeddings.

Question

Before we compare the wordnet and word embeddings at the end. I’d like you to think one question, which paused me for some time at first. WordNet can measure semantic similarity between words. How can we use them to detect semantic shift?

Hybrid!

At first I’m puzzled, because although the similarity is measurable and wordnet2vec embeddings are quantitative, it compares two different words, not the same word from different time period. And in fact I didn’t find research that only use Wordnet to analyze semantic shift, but instead, they are use as an complementary tool to optimize the performance of word embedding models, as shown below:

- WordNet + Word2Vec —> Retrofitting/Counterfitting (Faruqui, 2015)

- WordNet + BERT —> WN-BERT: Wnet2Vec + BERT (Barbouch, 2021)

- WordNet + BERT —> Clustering

Some combination like retrofitting works positively, while others like WN-BERT perform distinctively on different NLP tasks.

Takeaways

And finally some takeaways!

Wordnet is a lexical database of words with semantic relations, they are manually annotated. Static embeddings are vectors representing words in semantic space, with one vector for oe word, while contextualized embeddings are Vectors representing words in context, with many vectors for one word.

In summary they are all very useful for Semantic shift detection task, contextualized embeddings are the leading method, but how to make use of semantic knowledge in wordnet is also a valuable topic.

Literature

- Lilian Weng’s Blog-Learning Word Embedding, https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2017-10-15-word-embedding/

- Yoon Kim, Yi-I Chiu, Kentaro Hanaki, Darshan Hegde, and Slav Petrov. 2014. Temporal Analysis of Language through Neural Language Models. In Proceedings of the ACL 2014 Workshop on Language Technologies and Computational Social Science, pages 61–65, Baltimore, MD, USA. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Montanelli, Stefano, and Francesco Periti. A Survey on Contextualised Semantic Shift Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.01666 (2023).

- George A. Miller. 1992. WordNet: A Lexical Database for English. In Speech and Natural Language: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Harriman, New York, February 23-26, 1992.

- Chakaveh Saedi, António Branco, João António Rodrigues, and João Silva. 2018. WordNet Embeddings. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP, pages 122–131, Melbourne, Australia. Association for Computational Linguistics.